The poet Shelley described London’s shops in a letter

to Thomas Manning:

|

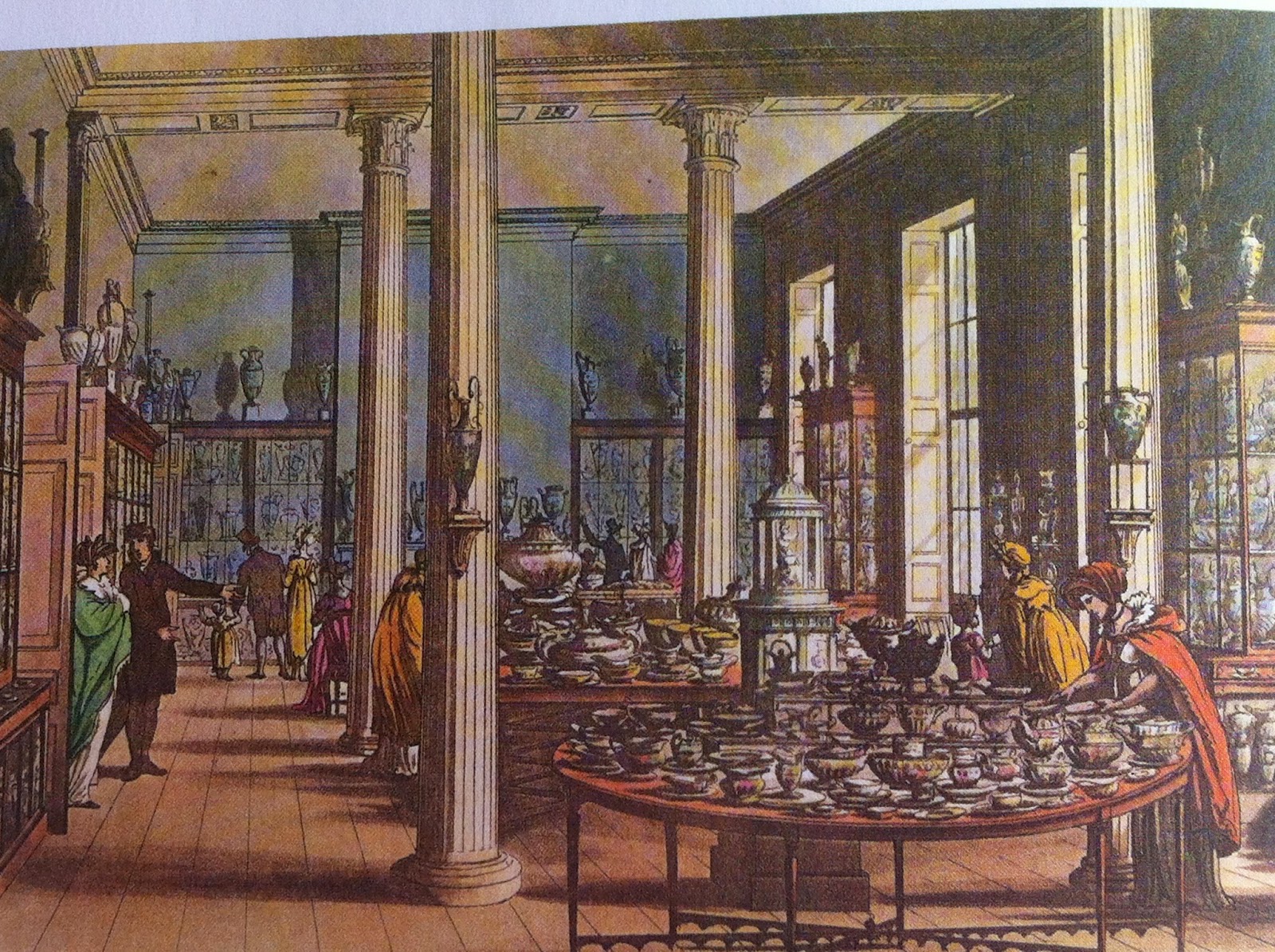

| Wedgwood |

‘Oh, the lamps of a night! her rich goldsmiths,

print-shops, toy-shops, mercers, hardware men, pastry-cooks, St Paul’s

churchyard, the Strand, Exeter Change, Charing Cross, with a man upon a black

horse! These are thy gods, O London!’

Most shopkeepers lived with their families above or

behind their premises. They were usually specialists in the goods they sold,

and very often the craftsman who made them – whether a shoemaker, tailor,

hatter, fan-maker, umbrella-maker or jeweller – often there was no distinction

between retailer and wholesaler. There were no regular shopping hours – the

shopkeeper opened his shop before breakfast and closed it before he retired for

the night.

Sophie von la Roche, a German novelist, wrote about

Oxford Street to her daughters in 1785:

We strolled up and down lovely Oxford Street this

evening, for some goods look more attractive by artificial light. Just imagine,

dear children, a street taking half an hour to cover from end to end, with

double rows of brightly shining lamps, in the middle of which stands an equally

long row of beautifully lacquered coaches, …

|

| Regent Street |

A few weeks later she wrote again: I found another

shop here like the one in Paris, containing every possible make of woman’s

shoe; there was a woman buying shoes for herself and her small daughter: the

latter was searching amongst the doll’s shoes in one case for some to fit the

doll she had with her. But the linen shops are the loveliest; every kind of

whitewear, from swaddling clothes to shrouds, and any species of linen can be

had. Night-caps for ladies and children, trimmed with muslin and various kinds

of Brussels lace, more exquisitely stitched than I ever saw before … People, I

noticed, like to have their children with them and take them out into the air,

and they wrap them up well, though their feet are always bare and sockless … I

was glad to strike some of the streets in which the butchers are housed, and

interested to find the meat so fine and shops so deliciously clean; all the

goods were spread on snow-white cloths, and cloths of similar whiteness were

stretched out behind the large hunks of meat hanging up; no blood anywhere, no

dirt, the shop walls and doors were all spruce, balance and weights brightly

polished.

Whether they are silks, chintzes or muslins, they hang

down in folds behind the fine high windows so that the effect of this or that

material, as it would be in the ordinary folds of a woman’s dress can be

studied. Amongst the muslins all colours are on view, and so one can judge how

the frock would look in company with its fellows. Now large shoe and slipper

shops for anything from adults down to dolls can be seen – now fashion articles

of silver or brass … absolutely everything one can think of is neatly,

attractively displayed, and in such abundance of choice as almost to make one

greedy …

Writing from her brother Henry's house in Sloane Street, on May 2 1813, Jane wrote: Your letter came just in time to save my going to Remnant's, and fit me for Christian's, where I bought Fanny's dimity. I went the day before (Friday) to Layton's, as I proposed, and got my mother's gown - seven yards at 6s. 6d. I then walked into No. 10, which is all dirt and confusion, but in a very promising way...I gave 2s. 6d. for the dimity. I do not boast of any bargains, but think both the sarsenet and dimity good of their sort. I have bought your locket, but was obliged to give 18s. for it, which must be rather more than you intended. It is neat and plain, set in gold.

In September she was staying in Henrietta Street where her brother Henry had recently moved. Instead of saving my superfluous wealth for you to spend, I am going to treat myself with spending it myself. I hope, at least, that I shall find some poplin at Layton and Shear's that will tempt me to buy it. If I do, it shall be sent to Chawton, as half will be for you; for I depend upon your being so kind as to accept it, being the main point. It will be a great pleasure to me. Don't say a word. I only wish you could choose too. I shall send twenty yards.

In Sense and Sensibility the Dashwood sisters go shopping in Bond Street, though Marianne is distracted, her thoughts are full of Mr Willoughby who she is hoping to see.

After an hour or two spent in what her mother called comfortable chat, or in other words, in every variety of inquiry concerning all their acquaintance on Mrs. Jennings's side, and in laughter without cause on Mrs. Palmer's, it was proposed by the latter that they should all accompany her to some shops where she had business that morning, to which Mrs. Jennings and Elinor readily consented, as having likewise some purchases to make themselves; and Marianne, though declining it at first, was induced to go likewise. Wherever they went, she was evidently always on the watch. In Bond Street especially, where much of their business lay, her eyes were in constant inquiry; and in whatever shop the party were engaged, her mind was equally abstracted from everything actually before them, from all that interested and occupied the others. Restless and dissatisfied every where, her sister could never obtain her opinion of any article of purchase, however it might equally concern them both; she received no pleasure from anything; was only impatient to be at home again, and could with difficulty govern her vexation at the tediousness of Mrs. Palmer, whose eye was caught by everything pretty, expensive, or new; who was wild to buy all, could determine on none, and dawdled away her time in rapture and indecision.

|

| Sackville Street |

I love reading about descriptions of shopping

experiences like those above, especially now the High Streets of Britain seem to be

losing their shopping streets bit by bit. It’s wonderful to be able to shop on

the internet, but shops here are finding it hard to compete.

However, Fortnum and Mason, Hatchard’s

Bookshop,

and Floris

the perfumers, amongst others, are still going strong – perhaps

because they’ve embraced online shopping too. Jane would have known these shops

and I hope they’ll still be here in London for another 200 years or so!